To understand why patellar luxation in dogs occurs, and how it can be treated, it is helpful to understand a little anatomy.

The quadriceps muscle is the large muscle at the front of the thigh and is responsible for extending the stifle (knee) joint. The patella (kneecap) is a bone that is attached to the underside of the tendon at the end of the quadriceps muscle. The patella holds the quadriceps in position at the front of the stifle joint. As the quadriceps expands and contracts, the patella moves up and down in a groove called the femoral trochlea.

Correct positioning of the quadriceps muscle is important to maximise the mechanical advantage (leverage) that is developed when the muscle contracts.

What is patellar luxation?

Patellar luxation means that the kneecap luxates (dislocates) from the femoral trochlea. The patella may luxate medially (towards the inside of the knee) or laterally (towards the outside of the knee).

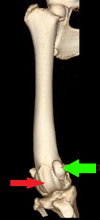

Figure 1. This shows a 3 dimensional model created using a CT scanner showing the femur and stifle joint of a bow legged Rottweiler with patellar luxation

Figure 1 is a 3 dimensional model created using a CT scanner showing the femur and stifle joint of a bow legged Rottweiler with patellar luxation. The patella (green arrow) should sit within the groove in the front of the femur called the femoral trochlea (red arrow). However, in this case the patella is sitting to the medial side of the femoral trochlea. This causes a massive reduction in the ability of the quadriceps muscle to extend the stifle joint and maintain a standing posture. Dogs will frequently become suddenly lame and may skip on the affected leg or appear to collapse when weight bearing. More severely affected dogs may have great difficulty standing or walking. If the patella slips back into position then the lameness will suddenly improve.

Will patellar luxation in dogs get better by itself?

Unfortunately, patellar luxation tends to get worse with time rather than getting better. This deterioration may involve the patella spending more and more time in a luxated position or be associated with the cartilage on the edge of the trochlea being rubbed away leading to the formation of painful cartilage ulcers. A grading system is often used where grade I is very mild (the patella can be pushed out but immediately returns to the groove) and grade IV is very severe (the patella is luxated and cannot be replaced).

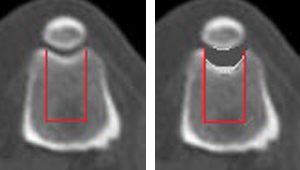

Figure 2

Why does patellar luxation in dogs happen?

Patellar luxation only occurs when there is poor alignment between the femoral trochlea and the quadriceps mechanism. There are many different deformities of the femur or tibia which may lead to patellar luxation but all result in the trochlea being poorly aligned with the quadriceps mechanism. Accurate recognition of the different types of deformity is important to choose the most appropriate treatment for each animal. As an example, the red line on Figure 2 represents the normal path of the quadriceps from the pelvis at the top of the picture to the insertion on the tibia at the bottom. When the patella is normally positioned in the groove, the quadriceps muscle is not straight and tension in the muscle results in the patella skipping out of the groove, so that the quadriceps lies in a straight line (fine green line). Realignment of the pull of the quadriceps is vital to the successful treatment of patellar luxation.

How is canine patellar luxation diagnosed and will radiographs (X-rays) be needed?

The diagnosis of patellar luxation is made by feeling the patella slip out of position, however in some dogs the patella can be seen in an abnormal position when radiographs are taken. X rays can certainly be useful to screen for other causes of lameness, however it can be difficult to accurately diagnose and measure deformities that cause patellar luxation such as femoral varus (inward bowing of the femur) or femoral torsion (twisted femur) using normal radiographs. To get around the shortcomings of X rays, I generally perform a CT scan of the hind-limbs so that I can create a three dimensional image of the skeleton that can be spun around and viewed from any angle. This allows more precise measurements to be taken and greatly improves the ability to be able to choose the best surgical procedure for each animal.

What treatment do you recommend for these slipping kneecaps?

Each case is slightly different, however most cases of grade 2/4 and above will benefit significantly from surgery. I normally perform a three step surgery for patellar luxation:

Step 1 – Realign the quadriceps mechanism

Achieving proper alignment of the quadriceps mechanism is absolutely vital to the success of surgery, and realignment of some sort should be performed in every case. This commonly involves moving the attachment of the quadriceps mechanism (tibial tuberosity transposition – Figure 3) but in more complex cases may involve femoral osteotomy (cutting the femur to straighten or untwist the bone – Figure 4).

Figure 3. Xray showing transposition of the tibial tuberosity to prevent patellar luxation in a large dog

The radiograph in Figure 3 has been taken following transposition of the tibial tuberosity. The bone at the front of the tibia has been cut and moved sideways before being held in position using two steel pins and a figure of eight wire. This realigns the quadriceps so that the patella no longer leaves the groove.

Figure 4

Figure 4 shows the postoperative radiograph of the Rottweiler seen in Figure 1 following surgery to straighten the femur. This involved cutting and straightening the bone, before the application of a bone plate and screws. The surgery was successful and the dog made a complete recovery.

It is important that the correct straightening procedure is employed in each case to prevent the patella being pulled diagonally across the trochlea rather than straight up and down the groove.

Step 2 – Trochleoplasty – (groove deepening)

Figure 5. CT scan showing a new deeper groove that will prevent patellar luxation and a slipping knee cap

Figures 5 shows cross sections taken through the femur and patella. Block recession sulcoplasty involves removal of the block of bone edged in red (image on the left). Additional bone is then removed before the block is replaced (image on the right). This creates a deeper groove that helps to retain the patella in position.

Step 3 – Adjust soft tissue tension

The patella is supported by the surrounding joint capsules and by medial and lateral retinaculae. These are essentially ligaments attached to the joint capsule that act as guy ropes on each side of the patella. In affected animals, the soft tissues will be loose/stretched on one side and tighter on the other as a result of patellar luxation occurring. Careful tightening of the stretched tissues and release of the tighter tissues can improve the stability of the patella in the trochlea and prevent reluxation from occurring. Again this should only be performed following realignment of the quadriceps mechanism.

What is the outlook for dogs with patellar luxation?

The prognosis following surgery is generally very good, providing the underlying cause of the deformity has been correctly identified and accurately treated. Unfortunately, if the underling deformity is not accurately identified and properly treated, patellar luxation surgery can be unforgiving and reluxation can often result.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.